Hickok, G., & Poeppel, D. (2004). Dorsal and ventral streams: A framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition, 92(1–2), 67–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011

- Paper gelesen?

- Infos rausgeschrieben?

Hickok & Poeppel (2004) - Cognition

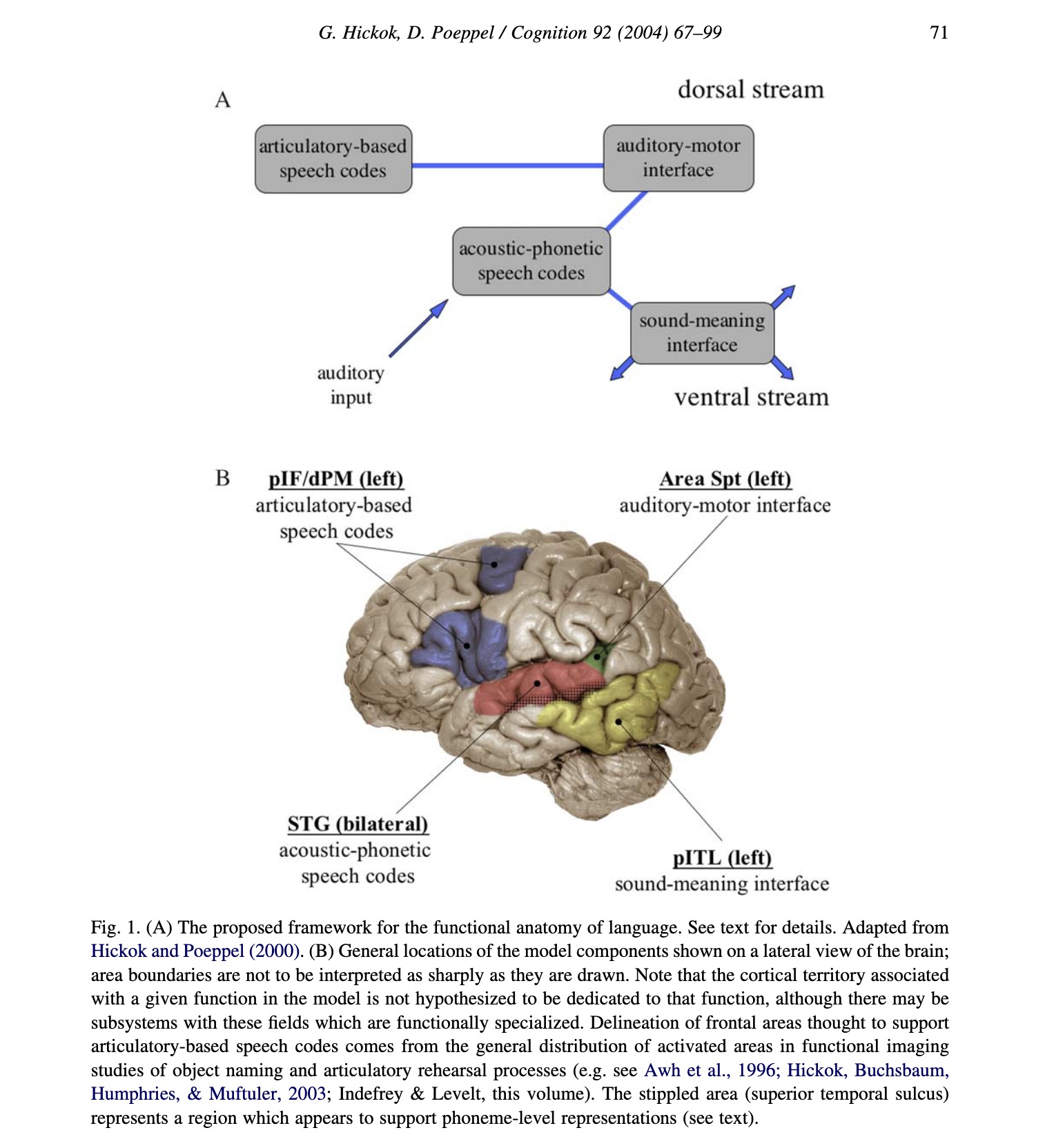

The functional anatomic framework for language which is presented in this paper is based on a rather old insight in language research dating back at least to the 19th century (e.g. Wernicke, 1874/1969), namely that sensory speech codes must minimally interface with two systems: a conceptual system and a motor–articulatory system.

- we will argue that sensory representations of speech in auditory-related cortices (bilaterally) interface (i) with conceptual representations via projections to portions of the temporal lobe (the ventral stream), and (ii) with motor representation via projections to temporal –parietal regions (the dorsal stream). Before presenting the detail

- In the last several years, however, there has been mounting evidence suggesting that the concept “where” may be an insufficient characterization of the dorsal stream (Milner & Goodale, 1995). Instead, it has been proposed that the dorsal visual stream is particularly geared for visuo-motor integration, as required in visually guided reaching or orienting responses.1 According to this view, dorsal stream systems appear to compute coordinate transformations – for example, transform representations in retino-centric coordinates to head-, and body-centered coordinates that allows visual information to interface with various motor-effector systems which act on that visual input (Andersen, 1997; Rizzolatti, Fogassi, & Gallese, 1997).

- While there is general agreement regarding the role of the ventral stream in auditory “what” processing, the functional role of the dorsal stream is debated.

- we have put forward a third hypothesis, that the dorsal auditory stream is critical for auditory – motor integration (Hickok & Poeppel, 2000), similar to its role in the visual domain

- ventral stream, which is involved in mapping sound onto meaning, and a dorsal stream, which is involved in mapping sound onto articulatory-based representations.

- The ventral stream projects ventro-laterally toward inferior posterior temporal cortex (posterior middle temporal gyrus) which serves as an interface between sound-based representations of speech in the superior temporal gyrus (again bilaterally) and widely distributed conceptual representations. The dorsal stream projects dorso-posteriorly, involving a region in the posterior Sylvian fissure at the parietal – temporal boundary (area Spt), and ultimately projecting to frontal regions. This network provides a mechanism for the development and maintenance of “parity” between auditory and motor representations of speech.

- Although the proposed dorsal stream represents a very tight connection between processes involved in speech perception and speech production, it does not appear to be a critical component of the speech perception process under normal (ecologically natural) listening conditions, that is, when speech input is mapped onto a conceptual representation.

- We also propose some degree of bi-directionality in both the dorsal and ventral pathways.

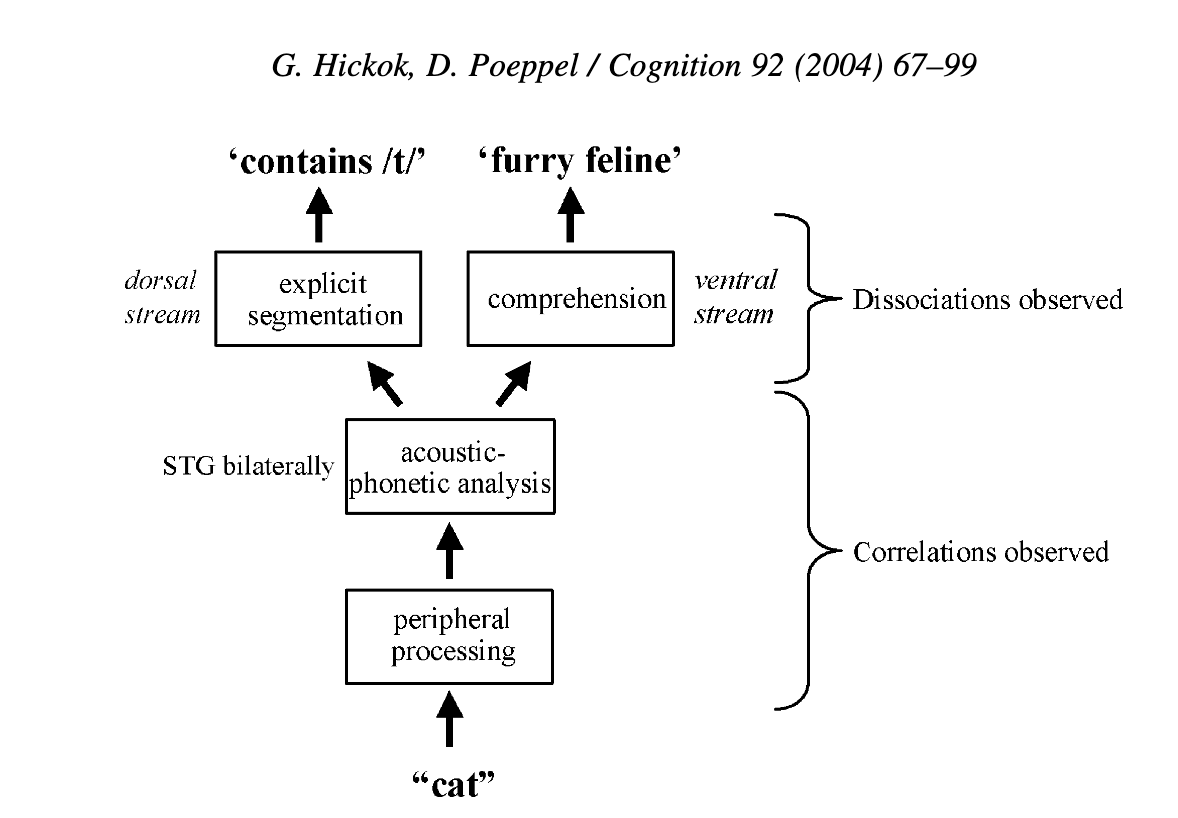

- Language processing systems can be viewed as a set of transformations over representations (not necessarily in series), for example, mapping between an acoustic input and a conceptual representation (as in comprehension), or between a conceptual representation and a sequence of motor gestures (as in production). Early stages of this mapping process on the input side – for example, cochlear, brain stem and thalamic processing as well as at least early cortical auditory mapping – likely perform transformations on the acoustic data that are relevant to linguistic as well as non-linguistic auditory perception. Because these early processing stages are not uniquely involved in language perception, they are often dismissed as being merely “auditory” areas and not relevant to understanding language processing. But clearly each stage in this analytic process interacts with other stages in important ways: the computations performed at one level depend on the input received from other levels, and therefore each transformation plays a role in the entire process of mapping sound onto meaning (or meaning onto motor articulation).

- An important consequence of this view of language processes as a set of computations or mappings between representations is that the neural systems involved in a given language operation (task) will depend to some extent on what representation is being mapped onto.

- For example, speech input which is mapped onto a conceptual representation (as in comprehension tasks) will clearly involve a set of computations which is non-identical to those involved in mapping that same input onto a motor articulatory representation (as in a repetition task). Of course, the mapping stages in these two tasks will be shared up to some point, but they must diverge in accordance with the different requirements entailed by the endpoints of the mapping process. The upshot is that the particular task which is employed to investigate the neural organization of language (that is, the mapping operation the subject is asked to compute) determines which neural circuit is predominantly activated.

- laut Hickok geht es vom “superior temporal gyrus (STG) bilaterally. This cortical processing system then diverges into two processing streams, a ventral stream, which is involved in mapping sound onto meaning, and a dorsal stream, which is involved in mapping sound onto articulatory-based representations.”

- ventral

- The ventral stream projects ventro-laterally and involves cortex in the superior temporal sulcus (STS) and ultimately in the posterior inferior temporal lobe (pITL, i.e. portions of the middle temporal gyrus (MTG) and inferior temporal gyrus (ITG)).3 These pITL structures serve as an interface between sound-based representations of speech in STG and widely distributed conceptual representations (Damasio, 1989). In psycholinguistic terms, this sound – meaning interface system may correspond to the lemma level of representation (Levelt, 1989).

- ventro-lateral portions of the STG, extending into both anterior and posterior portions of the STS, appear to respond best to complex spectro-temporal signals such as speech

- All of these observations suggest that cortex in ventro-lateral portions of the STG, including the STS (stippled portion in Fig. 1B), comprises advanced stages in the auditory processing hierarchy which are critical to phoneme-level processing

- dorsal

- The dorsal stream projects dorso-posteriorly toward the parietal lobe and ultimately to frontal regions. Based on available evidence in the literature (Jonides et al., 1998), we previously hypothesized that the posterior portion of this dorsal stream was located in the posterior parietal lobe (areas 7, 40). Recent evidence, however, suggests instead that the critical region is deep within the posterior aspect of Sylvian fissure at the boundary between the parietal and temporal lobes, a region we have referred to as area Spt (Sylvian– parietal – temporal) (Buchsbaum, Humphries, & Hickok, 2001; Hickok et al., 2003). Area Spt, then, is a crucial part of a network which performs a coordinate transform, mapping between auditory representations of speech and motor representations of speech

- ventral

- We also propose bi-directionality in both the dorsal and ventral pathways. Thus, in the ventral stream, pITL networks mediate the relation between sound and meaning both for perception and production

- Our claim is simply that there exists a cortical network which performs a mapping between (or binds) acoustic –phonetic representations on the one hand, and conceptual – semantic representations on the other.

- we hypothesize that sectors of the left STG participate not only in sub-lexical aspects of the perception of speech, but also in sub-lexical aspects of the production of speech (again, perhaps non-symmetrically).

- In the dorsal stream, we suggest that temporal –parietal systems can map auditory speech representations onto motor representations

- When the neural organization of speech perception (or acoustic –phonetic processing, we will use these terms interchangeably) is examined from the perspective of auditory comprehension tasks, the picture that emerges is one in which acoustic –phonetic processing is carried out in the STG bilaterally (although asymmetrically) and then interfaces with conceptual systems via a left-dominant network in posterior inferior temporal regions (e.g. MTG, ITG, and perhaps extending to regions around the temporal parietal – occipital boundary). The arguments supporting this claim follow in Sections 4.1 and 4.2. Sentence-level processes may additionally involve anterior temporal regions (see Section 4.4).

- while Wernicke’s area is classically associated with the left STG, Wernicke himself indicates that both hemispheres can represent “sound images” of speech. According to Wernicke (1874/1969), the left STG becomes dominant for language processes by virtue of its connection with the left-lateralized motor speech area

- Another line of evidence comes from imaging studies of “semantic processing” (typically lexical semantics) which generally implicate inferior posterior temporal regions and posterior parietal cortex (Binder et al., 1997).9 This distribution of activation corresponds quite well to the distribution of lesions associated with transcortical sensory aphasia (TSA) which lends support to the claim of meaning-based integration networks in posterior ITL (again perhaps extending to regions around the temporal –parietal – occipital junction).

- Taken together, these observations (including those from SD) are consistent with our claim of a sound –meaning mapping system in posterior ITL.

- Finally, Indefrey and Levelt (this volume), in their meta-analysis of a large number of functional imaging studies, have identified the middle portion of the MTG as a site which plays a role in “conceptually-driven lexical retrieval” during speech production; this region was also shown to be consistently active during speech perception in their analysis. This stage in processing is compatible with our sound – meaning interface.

- these data suggest a possible role for anterior temporal cortex in aspects of grammatical processing

see also

Tags: neuroscience science source

Superlink: 050 🧠Neuroscience

Created: 2025-11-12 22:16